I copied one ancient text out by hand for three years

Introduction: Three years of mornings with Patanjali

A few years ago, I wanted to break my habit of plowing through books one after another, and that nagging sense I was wasting my time reading aimlessly.

So I copied the Sutras of Patanjali every day for the past three years, a few lines at a time.

At some point, I began to think it was time to find a different book to use in my copying practice, but then I thought it would be great to try and list out as many insights as I could.

Here’s what I learned so far.

How I Got Started with the Quill

A few years ago, the low quality of my metacognition was brought sharply into focus. I was not using my thoughts very intentionally. Mostly I allowed my thoughts to fill up whatever shape I encountered. If I had work to do I tried to do it. If I was around people, I mostly allowed their moods and ideas to permeate my thoughts. I was easily swept away by my own emotions, usually having to do with regrets or fears.

These deficiencies placed me in a career timeout, a dead zone. On the negative side, I was trying not to panic — I had mouths to feed. On the plus side, I had a little more free time. Fortunately, I decided to design a day starter routine for myself. While Internet influencers were pushing 4am routines with cold-showers and yak butter coffee, I trudged out to my back yard with pen and paper and a copy of something to copy out.

I knew that journaling would be a good thing to do daily. But I also knew from experience that if I only used journaling, I ran the risk of reinforcing my habitual thoughts, choking on stale air. I remembered how much fun I had as a language learner, taking dictation, or copying phrases from the board.

After some experimentation, I found my special recipe to put me in a calm, productive, and creative frame of mind: I’d do 3 pages of longhand journaling, half a page of copying, and some breath work.

I ended up calling it The Cave, the Quill, and the Whale.

Finding a Book with Quill Potential

Having already devoured lots of mass market paperbacks on productivity, organization, and generally getting your shit together, I felt like spending time with books whose value had been confirmed by generations. I started calling them Old Growth Books.

Fishing through what I had on hand, I started with the poems of Emily Dickinson (perfect length for copying — and each one posed a question or offered an insight), cycled through Plato’s Republic (juicy, funny, but too impossible to make bite-sized), and settled on the Sutras of Patanjali, translated by Allistair Shearer. This fit all the requirements for this little day-starter I was building: deep thoughts whose value had been confirmed over thousands of years, presented in short verses I could unpack and contemplate, a few at a time.

I figured I could copy down all 196 sutras over a few weeks, then zip back to the Republic, which I’d always planned to dig deeper into. (I had not really internalized the value of slow reading yet.)

I ended up spending more than 3 years with this one little book. I still feel like I’m just getting started. I’ve read lots of other books in between, for reference, for pleasure, or for work. But working quill-style, copying out a book a little at a time, has been really refreshing, and has given me a new appreciation for what it takes to actually live with a book for a while.

I have set down some thoughts on the ideas I’ve spent the most time with. I hope this will inspire you to take up your own slow-reading project, whatever the source.

The Unsettled Mind

1.2 Our essential nature is usually overshadowed by the activities or the activity of the mind

Does anybody ever actually set off to discover his true nature?

I didn’t. This exercise was about trying to solve my problems: I had trouble making decisions, getting along with people, getting the right things done.

As I worked to try and address these problems using my morning ritual, two things became pretty clear:

- Quick fixes only look good if you’re in a hurry

- Being in a hurry is the worst way to solve any problem

That’s not to say problems don’t have to be solved when you’re in a hurry. But the fixes you have at your disposal are only as good as the decisions you make while you’re not in a hurry.

Let’s say that your essential nature is your ability to make the best decisions possible. If the activities of your mind are overshadowing your essential nature, then recognizing and settling those activities is a simple and direct way to make better decisions.

Put an even blunter way, if your kitchen table is covered with unpaid parking tickets, you need to start meditating right now. This could mean you do silent, seated meditation, the way it’s mostly described. But it could be a 15 minute silent walk around your block without your phone. It could be 100 slow jumping jacks. Or three pages of handwritten journaling.

Will meditation miraculously pay all your parking tickets? It will not. Also, trying to establish a consistent meditation practice while you’re stressed out about the parking tickets will feel like shit at first. But if you can gradually train your mind from reacting quickly to reacting just a bit more slowly, the effect will seem miraculous.

Jumbled thoughts

3.17: Perception of an object is usually confused, because its name, its form, and an idea about it are all super-imposed upon each other

After reading and copying this line a few times, I started thinking of how I could practice this to unscrew my thinking about the most important people, places, and things in my life. Since making a start with this, I’ve already noticed lots of ways in which I was confusing things, mixing things together in my mind, superimposing things that were not necessarily connected.

For example, I recently went to my high school reunion. With each person I re-encountered, I tried to affirm to myself that I never really knew this person, and even if I did once, so many years had passed that we had both become completely new and different people. As a result, I never felt that nagging sense of awkwardness I sometimes feel when talking with folks I’ve known for a while. I felt myself listening comfortably to what each person said, and felt no pressure to agree or disagree.

Mental Activity Can Be Classified

Building on the idea that your essential nature is usually overshadowed by the activities of the mind, these lines propose a scheme for itemizing them.

1.5 There are five types of mental activity. They may or may not cause suffering.

1.6 These five are:

understanding

misunderstanding

imagination

sleep

and memory

Ever since I realized that my metacognition sucks, I’ve been looking for ways to improve the way I think. The way mental activities are listed and grouped in the Sutras sets a powerful example of thinking clearly and with purpose, and helped me let go of some of my ruminating and obsessing.

I appreciate the moral neutrality of these terms, which stands in contrast to the religiously fervent self-scrutiny I was lectured on about when I was young. Self-examination takes on too much weight when the prospect of everlasting torture is on the line. Here we’re just looking under the boat to smooth out the contours, reduce friction, maybe patch a few leaks.

Making Use of Granularity

Later in section 1, we get some more ideas on how to settle the activities of the mind:

1.35 Experience of the finer senses establishes the settled mind

When I first came across sutra 1.35, the idea of fine smells and tastes did not seem super-interesting. But the idea of cultivating finer levels of discernment led me to think about emotions, which can have fine or coarse levels, just like flavors.

I was raised in an environment where extreme thinking was pervasive. A small mistake such as failure to complete a household chore was met with extremely harsh moral judgment. I grew into a person who reacted in extreme ways to minute challenges. I would have extreme emotional reactions when I ran into a simple challenge, and was often thrown off course.

Then I learned the term ‘emotional dysregulation,’ and the shoe fit. Since then, I’ve been wondering if I could learn to regulate my emotions more finely. Instead of getting really angry instantly, I could try noticing smaller levels of irritation, and maybe do something to change the situation before the feeling got out of proportion.

I now have a trailing awareness of the intensity of my responses to daily life events, and the beginnings of the ability to respond with less brute force and more curiosity.

The Real You, and the Explainer

As I said earlier, I didn’t set out to discover my true self. I just wanted to solve some problems I was having making good decisions, getting along with people, and getting things done.

But I was discovering that these problems all had a contributing factor in common: my mental model of the self.

Remember in section 1, that reference to the ‘essential Self’ that is overshadowed by the activities of the mind? In 2.20 we get a more precise definition of that term.

2.20: The Self is boundless. It is the pure consciousness that illumines the contents of the mind

The question here is “Who are you, really?” I’ve usually heard this as “Are you a good person, or are you some kind of fraud, or are you just fine the way you are?”

But this is a different kind of question, and it’s worth pondering for a moment. It’s more like “What is the core of who you’re being?”

Or even, ‘What is You, and what is Not-you?”

The Sutra expresses a point of view about this, but in order to consider this, I had to think about my own point of view, to get some clarity about how I’d been answering this question so far.

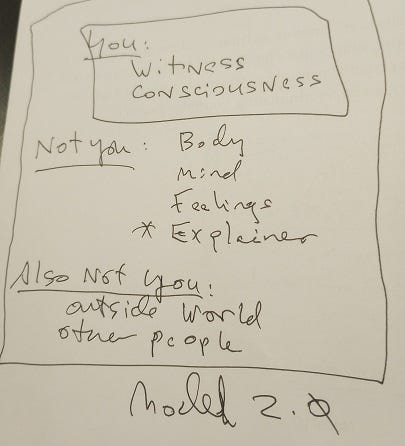

I call this Model 1.0.

In this model, you is made up of everything inside your skin bag: your body, your feelings, the contents of your mind, and that inner monologue, the Explainer.

The Explainer sits at the intersection of your picture of reality and the stream of input your senses are taking in, and tries to weave these together in a stream of internal language. You’ve been hearing this voice in your head since before you can remember. It’s not hard to notice, but it’s hard to shut off. In fact, one reason mentally ill people can be scary is that they sometimes verbalize this stream, and it reminds us of our fear of losing control of this voice.

You can drop a penny down the well anytime you like, just to see who’s really in charge. Try making your Explainer say “hello!!!”

There. You exerted control over the Explainer.

Not so easy to make it stop talking, though.

The Explainer keeps droning on from the moment you wake up to the moment you fall asleep. It’s obviously useful. The danger is, it’s easy to over-identify with this voice. If you think this is the most essential part of you, every time you hear it say random, crazy, awful, incriminating things, you judge yourself.

But you can take the view that this Explainer is just a benign process running in your mind, weaving things together, remembering things, imagining things, and — if you’re me — making the occasional crank call.

If this voice actually is you, and it sounds crazy or miserable, that’s one kind of problem. Now you have to medicate it, heal it, feed it better thoughts, discipline it, shut it up, and somehow try to disinfect the source of those insane ramblings that seem to arise at just the wrong moment.

But if it’s just a process, that’s a different kind of problem. You’ve still got all the sensory inputs, thoughts, and feelings to deal with. And the Explainer is still there.

But now you’re just dealing with the wake of a boat in the water, instead of the boat itself. You can observe it with a bit of detachment. Sure, feed it some affirmations, write down what it says — there might be a good song lyric in there somewhere among the ramblings.

What is significant about model 2.0 is what it defines as the essential Self: simply that conscious process witnessing everything that is happening, including your sense input, your feelings, what’s going on in your mind, and including the Explainer.

But the sense impressions, feelings, thoughts? Not you. Just the contents of the stream you’re witnessing.

The outside world? Also not you.

So what? What’s so great about model 2.0?

If you can spend some time thinking about Model 2.0, you can develop some detachment from all the sensory input, the feelings, the thoughts that take up so much of your daily experience.

And of course, this can give you some detachment from the Explainer.

You can also take a few minutes to think about what the essential Self is like. Can it experience fear? Or grief? Can it become bored? Irritated?

You can think about the words Witness and Consciousness.

If this essential Self has the ability to witness, can you spend any time trying to allow that part of your mind to work, keeping the mental activities from grabbing control and stealing the show?

If you’ve ever been instructed to meditate by watching your breath, you can try watching yourself take and release breaths as a conscious witness. If you count out 30 breaths this way, your meditation practice will flourish.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. But it’s a start.

The 3-step dance of Sanyama

Sanyama is a keystone concept in the sutras — a building block for other ideas. But taken alone, it’s a beautiful and useful pattern to think about.

I try to avoid jargon from other languages, but I don’t know of any good English terms for the stages described here:

3.1 When the attention is held focused on an object, this is known as dhāranā.

3.2 When awareness flows evenly toward the point of attention, this is known as dhyāna.

3.3 And when that same awareness, its essential nature shining forth in purity, is as if unbounded, this is known as samādhi.

3.4 Dhāranā, dhyāna, and samādhi practiced together are known as sanyama.

I find this pattern of sanyama useful for recruiting my mind to do anything — learning, creating, accepting, imagining. First you bring your attention to a thing, then direct your awareness to it, and then you stay there until you notice something else happening — your awareness has expanded.

You can easily try it by counting out 100 breaths while looking at a candle flame, or watching a patch of grass in the wind, or some waves in the water. After a few minutes with focused attention and then awareness of an object of attention, the process of your mind changes.

This pattern works in large and small ways, over moments and years.

It’s what happened when I spent 3 years copying the sutras out by hand.

What began as fun busywork became a conversation with an ancient community that seems to have just begun.

Sanyama forms an elegant container for all the great 3-stage patterns that have attracted my imagination through the years:

Mamet’s description of three-act structure. Hegel’s Thesis/Antithesis/Synthesis. The Trinity I learned from the Catholics, and on and on.

Patanjali’s description of Sanyama lights up my mind because I see it as the process my mind SHOULD be able to follow when conditions are right. But without appreciating this process, it’s easy for me to short change my health by neglecting to set the stage.

Each of us has a recipe for sanyama, maybe lots of different ones, maybe a living cookbook, one that grows along with us.

When I was young, my father’s tuneless whistle was the sign he was focusing on painting, and allowing his mind to expand onto the canvas and make terrific, imaginative scenes and portraits.

For years, my children have practiced a form of outdoor meditation called Sit Spots, where they sit at the edge of a clearing for hours, noticing the cadence of bird calls, tracking the movement of animals, and allowing their awareness to expand beyond the confines of their physical body.

When I was 15, I reached the flow state while playing music in front of hundreds of people. Guitar in hand, in time with my garage band pals, I focused on the listeners and dancers, and time would skid forward at a totally different rate than normal. These days, I enter a state of weird and deep absorption after a few minutes with pens, a notebook, and some deep breaths.

Summing up

I’ve only touched a hint of the wealth of insights and wisdom stashed in this very old book. I am sure I’ll come back to it in the future.

It’s the first book I’ve unpacked this way, deliberately, one line at a time, at a pace more in keeping with the way it came to be in the first place: spoken, incanted, remembered, refined, condensed, organized into verses, copied out by hand countless times over, and then finally translated with care and published in my language.

Using this slow-reading method has enabled me to practice taking in ideas more carefully, made me a more careful thinker, and — I hope — a better listener to myself and others.